Ever since I was a child, when I think of holidays, Children’s Day and Culture Day come to mind.

I have a strong impression of Bunka no Hi for some reason, aside from Children’s Day, and I feel that it is not only because it is a fixed date holiday on November 3.

Click here to learn Japanese language with the best one-on-one Japanese tutoring lessons in online

In this page, we will look at the meaning and origin of Culture Day, as well as its “special day.

Contents

What is the meaning of Culture Day?

Culture Day is a national holiday, which is designated to “love freedom and peace and promote culture.

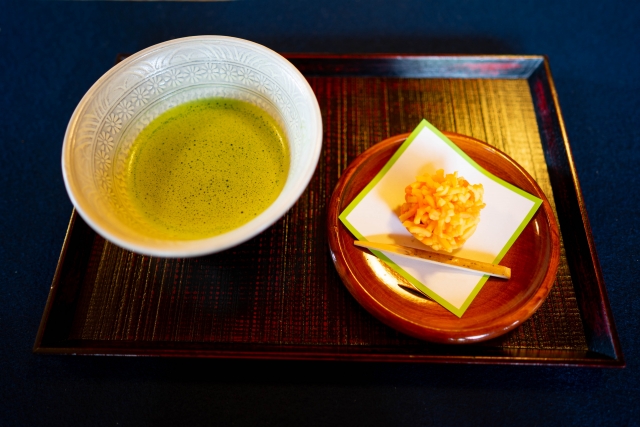

On Culture Day, various culture-related events are held, such as the awarding of the Order of Cultural Merit at the Imperial Palace and free admission to museums.

Yabusame (horseback archery) is also held at Meiji Shrine in Tokyo.

So what happened on November 3?

It was the date of the promulgation of the Constitution of Japan in 1946 (Showa 21). Before that, it was a national holiday called Meiji-Jissetsu.

As the phrase “Meiji no Bunmei Kaoka” (the civilization of the Meiji period) suggests, Meiji-betsu and Bunka-no-hi (Culture Day) are close in image.

However, when it comes to “Constitution” and “Culture,” one feels a little uncomfortable. This is probably because there is a “Constitution Memorial Day” on May 3, so does November 3 also have something to do with the Constitution? (May 3 is a Constitutional Day. (May 3 is the day the Constitution began to be implemented.)

And many things happened before November 3 became “Culture Day.

Let’s take a look at it in the next section.

Origin and History of Culture Day

First of all, please see the table below for the history of November 3.

| Western (Japanese) calendar | 祝日の名前 |

| 1873(明治6年) | 1911年(明治44年) | Tencho-setsu |

| 1927年(昭和2年) | 1947年(昭和22年) | Meiji-setsu (Meiji section) |

| 1948年 | | Culture Day Holiday (Nov 3) |

November 3 first became a national holiday in 1873, when it was called Tencho’s Festival.

Later, Tenchoseki was once abolished, but was restored in 1927 under the name of Meiji-bushi.

However, Meiji-bushi was abolished again in 1947. This was due to the will of GHQ (General Headquarters) after World War II.

GHQ (GHQ) was the Allied military agency that implemented the occupation policy of Japan after World War II (enforcement of the Potsdam Declaration, which called for Japan’s unconditional surrender, etc.), and was made up of a majority of American military and civilian personnel.

Its official name is General Headquarters, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, abbreviated as “GHQ” or “Occupation Forces.

The first Supreme Commander was Douglas MacArthur, with his trademark cornpipe and sunglasses.

The following year, in 1948, it became a national holiday called Culture Day. However, Culture Day did not come about easily.

The Japanese side has had considerable difficulty in establishing this Culture Day in 1948.

Although it is stated that “Culture Day has no direct relationship with the Meiji Festival,” there is clearly a will on the part of Japan to preserve the Meiji Festival.

November 3, a holiday that was once abolished, cannot be made a national holiday without a reason. Therefore, the date of the promulgation of the Constitution was intentionally set on November 3, and this day was made Constitution Day.

However, the GHQ again pressured them to do so. They were concerned that the people would perceive November 3 as “Constitution Day” and demanded that the name be changed. In other words, GHQ said

Constitution => State/Emperor => Meiji-betsu

In other words, GHQ did not want the people to associate the day with the “Constitution => State/Emperor => Meiji-betsu”.

As a result, the name “Culture Day” was established as a national holiday. In other words, November 3 was given a name that had nothing to do with the Constitution or the Emperor.

However, despite the name change, November 3 remains a national holiday. We should remember the Meiji era and pass it on to the next generation.

November 3 is a special day for fine weather.

Although not directly related to Culture Day, there is something that caught my attention while researching.

November 3 is a special day of fine weather.

A singular day is a day when a specific weather condition (weather, temperature, sunshine hours, etc.) appears with a very high probability.

This is a globally accepted concept.

Looking at the weather records for November 3, it is true that there were many sunny days before World War II, and not a few rainy days in the 1950s, but since then, there have been many sunny days again.

If you ask me, the weather was certainly better around the time of Culture Day, and I don’t remember it ever raining on that day.

It is an interesting phenomenon that the same day is almost always sunny every year.

However, there are several hypotheses as to why the singular day occurs, but none of them have been elucidated as of yet.

Conclusion

- November 3 was originally a holiday called Tenchousetsu, which celebrated the birthday of Emperor Meiji.

- Later, it was once abolished, but became a national holiday again as Meiji-betsu.

- Currently, it is a national holiday called Bunka no Hi (Culture Day).

- November 3 is also designated as a “fine weather day”.

Crror observing Bunka-no-hi is November 3. Originally, it was for observing the birthday of the Meiji Emperor, but now it is a national holiday dedicated to On this day, along with cultural and arts festivals held by each school and regional society, the government confers cultural service awards on Bunka-no-hi.

On this day, along with cultural and arts festivals held by each school and regional society, the government confers cultural service awards on individuals who have contributed to Japanese culture.

In particular, the Imperial Palace confers the Order of Cultural Merits on people who have rendered special service for the development of Japa

Related article: